“Leeds back then was very black and sooty,” says Alan Bennett. “When I first went to Cambridge, it just seemed like something out of a fairy story. It just looked so wonderful.”

Though these words might not be altogether loyal to the city of his birth, Bennett has done more than most to put Northern England, and Leeds in particular, on the map. With a few notable exceptions, his plays, monologues, screenplays and novels are distinctively Northern. The History Boys is no different, telling as it does the tale of seven working class Northern sixth formers who are studying for places at Oxbridge. Bennett admits that the story has its roots in his own life.

“I went to Leeds Modern, a state school, and they didn’t normally send students to Oxford or Cambridge, although it did often send pupils to Leeds University. But the headmaster happened to have gone to Cambridge and half a dozen of us tried and we all eventually got in.”

Unlike the characters in his play, the film version of which hit cinemas last week, Bennett couldn’t have cared less about Oxbridge.

“It wasn’t the Holy Grail,” he says, “in the sense that I’d never been to Oxford or Cambridge. Also, unlike in the play, the masters at my school had no idea what was expected of us during the entrance exam so we just had to busk it, really.”

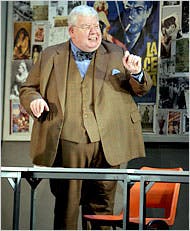

The History Boys has been an incredible adventure, and not just for Bennett. Directed by Nicholas Hytner, who also worked on play and film of Bennett’s The Madness Of George III (famously renamed The Madness Of King George for its cinematic release, lest dull-witted Americans think its the third in a trilogy), it was an instant hit when it played at London’s National Theatre. A film version was greenlit, starring every principle actor from the stage version. Once shooting was over, the production moved on to a triumphant Broadway run, garnering awards galore, including a Tony for Richard Griffiths. His troubled teacher Hector, who believes in learning for the sake of learning, is an astonishing creation. Was it, like many of Bennett’s parts, written with him in mind?

“No,” says Bennett. “I had no idea who could play Hector, no notion, really. And then Richard came to see us. As soon as you’ve chosen somebody, it obscures anybody else who you might have thought of. It’s like going to a place where you’ve never been and having a picture of it in your head and then going there in real life and having that picture wiped out by reality.”

Griffiths does indeed inhabit the role completely, although his own experience of academia is a million miles away from Hector’s.

“I went to the drama school at what became Manchester polytechnic,” he says. “I was working in Littlewoods in Stockton-on-Tees and handling money and being very good at mathematics. They sent me off to college to get some qualifications so I could come back and be a manager. I did an arts course instead. I didn’t know what I was doing. I just blundered into it.”

That blundering led to a celebratory career that has seen him become one of the UK’s best known actors. And, with The History Boys’ success in New York – which garnered Griffiths a Tony Award – he’s set to become famous in the States for more than just being Harry Potter’s nasty uncle. But the child-hating side is something he likes to play on. He talks of his eight young co-stars with mock vehemence:

“I don’t think those boys know the meaning of the word respect. There was certainly no visible demonstration or awareness of the word. The insults they used were usually fairly scatological and involving issues of personal hygiene and sexual mores. I would have them all beaten regularly.”

Of the eight boys, the best known is James Corden, a familiar face from films such as Mike Leigh’s All Or Nothing and Kay Mellor’s TV drama, Fat Friends. Cheeky and confident, he’s the very embodiment of the youthful impetuousness that Griffiths pretends delights in finding so infuriating. As Corden explains, it was all done out of love:

“When you find yourself working with people who have had such an impact on you growing up,” he says, “there are two things you can do: you can either put them on a pedestal or you can take them down a peg or two. We thought the best way to show our love and respect was to be absolutely vile and horrible to them.”

Bennett finds this both hilarious and understandable.

“The writer is quite low down on the hierarchy, really” he says, “but the fact that they took the piss out of Nick, who is also the director of the National Theatre, I would have thought was slightly more risky. They might never work again.”

Considering the success of The History Boys, this seems unlikely. Indeed, even if the film isn’t a huge box-office success, their lives will never be the same again. Corden is philosophical.

“Whatever happens in the future, I know that we’ve had this amazing time and I’ve spent two years working with seven other people who will be my friends for life. And that’s not just luvvie speak, that’s genuine. If we didn’t all get on, none of us have been contractually obliged to go with the project all the way; none of us had to go to New York, none of us had to sign on to do the film. But we all did.”

He does admit that there have been a few arguments.

“You’ve got eight young egos thrown together – you’re bound to have a few fights. There’s been a point when I’ve hated every single one of them, but it never lasts long. One thing is, if you’re throwing a fit, you’ll have seven people laughing at you and calling you Diana Ross.”

For Bennett, it takes him back to his own early career in the 1960s, when he first became a household name writing and acting in Beyond The Fringe.

“I spent three and a half years working closely with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore and, even though we didn’t see each other that often afterwards, whenever we did we went back to that relationship because we had that shared experience. That wasn’t so good for me, because back then I was always the one who got sat on.”

Though he delivers this last with a wry smile, one senses that he’s acutely aware that everyone in his anecdote is dead. Always of a morbid bent and a notorious hypochondriac, Bennett seems more aware of mortality than ever, especially given his recent revelation that, back in 1997, he almost lost his life to colon cancer. He’s even unwilling to properly enjoy the success of History Boys.

“Being a writer, you’re always thinking about what to do next,” he says. “It’s much easier to follow something that hasn’t been as successful. Success slows you down, really. But at the moment I’m very conscious that I’m getting on a bit. I just want to get as much done as I can.”

This feature first appeared on the FilmFour website in 2006