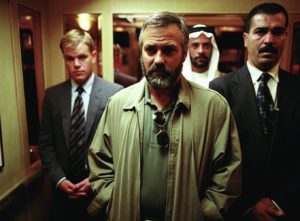

For George Clooney, 2005 was a hell of a year. And not just in a good way. Yes, he’s been nominated for three Oscars (Best Supporting actor for Syriana, Best Director and Best Screenwriter for Good Night, And Good Luck), but he also got to see what his own spinal fluid looked like. When it was coming out of his nose. On top of that, the USA’s rightwing continued to use him as a punchbag.

“You have to take your hits,” he says laconically in his deep, rumbling (some might say dreamy), Kentuckian drawl. “I can’t demand freedom of speech and then say, ‘But don’t say bad things about me.’”

Hits he most certainly did take. For his anti-Iraq War stance he was “pigeonholed as a traitor” by rightwingers.

“This made me mad,” he chuckles. “So I made these two films.”

While Good Night, And Good Luck, a superb reconstruction of Ed Murrow, the broadcaster who went head-to-head with Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, was very much Clooney’s baby – he wrote, directed and produced – the man behind Syriana was Stephen Gaghan.

Born in 1965, five years after fellow Kentuckian Clooney, he’s a slim-built, good-looking guy with blue eyes and blonde hair. Having won an Emmy for writing NYPD Blue and an Oscar for Traffic, he’s one of Hollywood’s most respected scribes. He’s incredibly serious, although his speech is peppered with mordant qu ips.

ips.

“I got the name Syriana from an overheard conversation when I was at the Pentagon, researching the film,” he says. “It was early ‘02 in Washington. These people had taken over the White House in 2000 and they had big plans for the Middle East. It was a heady day of Empire and they were talking about their policy in the Middle East. It wasn’t about Iraq, it was about Iran, Syria and the possibility of re-drawing the map, yet again. They were talking about making a new county and said it could be called Syriana.”

He laughs, adding:

“It’s funny that on the poster George has got Syriana written right across his forehead; it means ‘asshole’ in Japanese.”

A highly complex film, following the trail of corruption and money that oil spreads around the world. Characters include energy company CEOs, middle men, lawyers, disillusioned oil field workers seduced by Islamic fundamentalism and Clooney’s washed-up CIA agent. Opposite him is Prince Nasir, first in line to the throne of a fictional oil-rich country. A moderate Muslim and progressive thinker, he’s dismayed at the way in which none of the money generated by oil has filtered down to the people. He is determined to steer his country towards democracy and a less rampant form of capitalism. This doesn’t go down well with the US government.

“In a way,” says Alexander Siddig who plays Nasir, “my character isn’t just for the West to see, it’s for the Arab people to go, ‘Oh no, wait, you don’t have to be a crazy screaming guy to be intellectual’. Sadly I don’t think many Arabs will see it but may eventually get the DVD. In fact, they’ve probably already got it.”

While both Siddig and Clooney have their take on their own character, as the man responsible for every aspect of Syriana, it’s Gaghan who wraps his head around the big picture. Just how big the subject of oil is as it relates to America’s military-industrial complex came to him when he was at the Pentagon.

While both Siddig and Clooney have their take on their own character, as the man responsible for every aspect of Syriana, it’s Gaghan who wraps his head around the big picture. Just how big the subject of oil is as it relates to America’s military-industrial complex came to him when he was at the Pentagon.

“I went to see the deputy secretary of defence who was running the bureau of counter-narcotics,” he remarks, matter-of-factly. “It’s so big in there it’s like it’s hallucinogenic. The hallways are so long – you’ve never been in a hallway like this before. You can’t make out the end of it. Jesus, I thought, the American military is a large operation. And I went to this room and the sign on the door said ‘Bureau of counter-narcotics and counter-terror’. After the fall of communism, the system was just trying to find another reason to exist, so it finds the War on Drugs – a war against brain chemistry – and then the War on Terror. Both wars on abstractions. When the World Trade Centre came down, I knew then that George Bush was going to turn it into a giant war, not just a police action.”

As neither Gaghan nor Clooney are fans of Dubya, it’s a little surprising to find that Syriana was bank-rolled by Warner Bros., a company that, as part of AOL-Time-Warner, back Bush’s Republican party to the hilt.

“I was surprised Warner Bros. stepped up,” admits Clooney. “It was green-lit two years ago and back then the climate in America was very dark. It was like McCarthy in a sense. People would come to me and whisper, ‘I agree with you’ and I’d go, ‘Why are you whispering?’ Everyone turned into chickenshits.”

For Gaghan, it wasn’t just that Warner Bros. financed the project that amazed him.

“I was surprised they let me do it,” confesses Gaghan. “Two hundred twenty locations, four continents, five languages, 400 speaking parts. The scale of it for a second time director was, on paper, impossible. But that’s not the way it works out. With a movie it doesn’t matter what size it is, the problem is just the same: what the fuck is this scene about?”

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the ongoing folly in Iraq, Clooney is happy to report that the situation is a lot better. “Bush has a 38 percent approval rating,” he beams.

But, as a quick online search reveals, George’s popularity isn’t that high with people for whom ‘liberal’ is a dirty word.

“What the hell’s wrong with ‘liberal’?” he spits. “We’ve got blacks being allowed to sit in the front of the bus, we thought McCarthy was a schmuck, we thought Vietnam was wrong, we thought women should be allowed to vote… when have we been on the wrong side of a social issue? And yet they’ve demonised the word ‘liberal’.”

Siddig, well known to Star Trek fans as Deep Space Nine’s Dr Julian Bashir, has a much more global perspective on the issues raised. Born in Sudan, the nephew of the then Prime Minister, he was forced to flee aged just eight after a military coup.

“I was literally bundled on a plane and sent off to England where my mother already was,” he recalls. “At Heathrow airport I stayed with this British Airways stewardess for eight hours while they tracked down who I was from my passport. But Sudan has all the elements of Islam in one place – there are fundamentalists living alongside a more accessible, moderate version of Islam. And there’s a lot of oil there, too.”

While Gaghan “could care less” about right-wing critics, Clooney’s higher profile means he’s still a target. None of this has made his tough year any easier. In fact, if the majority of Clooney’s detractors weren’t rabid Christians, one might suspect they’d targeted him via voodoo. On the last day of shooting Syriana, he fell victim to a freak accident. Those with weak stomachs might want to look away now.

“In the torture scene,” he explains, “I threw myself over the back of a chair I was taped to. I hit the back of my head and damaged the wrap around the spine that holds it together. I was losing spinal fluid, which doesn’t hurt your back but makes your head feel like you’ve eaten ice cream too fast. That’s because what holds your brain up is spinal fluid, and if you haven’t got enough your brain sinks and the spinal fluid comes out – out though the nose.”

That must have put paid to his legendary partying.

That must have put paid to his legendary partying.

“I go to bed at nine o’clock every night now,” he says. “It’s called positional: the longer you’re up, the more your brain sinks so as the day goes on your head hurts. It’s hopefully getting better but I still have to do blood patches – they take 30cc of blood and they shoot it into my spine. And that hurts.”

He’s half relishing telling the story for the look of horror on my face. But afterwards, he slumps a little and looks tired.

“It’s been a very difficult year,” he says. “Everybody has that year when they age ten, and this was that year for me.”

Here’s hoping he at least gets one Oscar for his trouble. Even without the injury, he deserves it.

This article was first published on the FilmFour website in 2005.