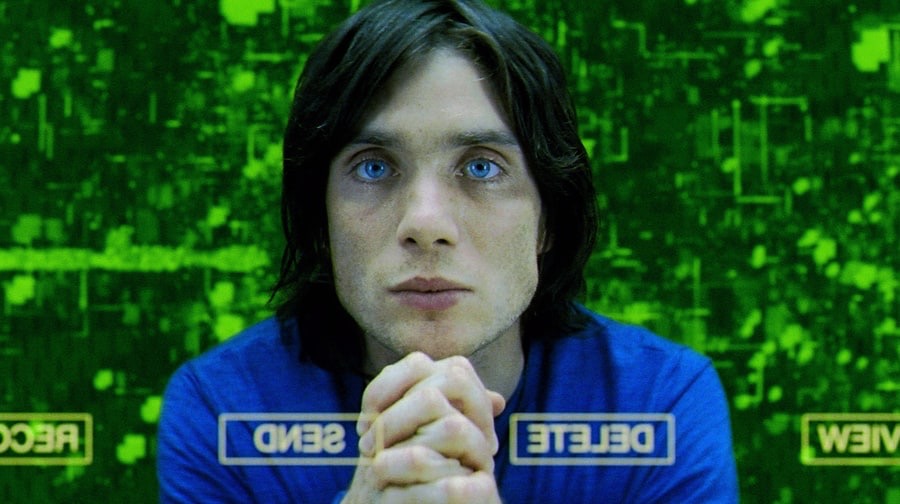

By the very nature of their profession, actors are paid to pretend, but it’s not often – on film at least – that they have to make believe they’re looking at the Sun without it actually being there. But, when he says, “The Sun was all put in afterwards in post-production”, Irish-born Cillian Murphy isn’t joking.

By the very nature of their profession, actors are paid to pretend, but it’s not often – on film at least – that they have to make believe they’re looking at the Sun without it actually being there. But, when he says, “The Sun was all put in afterwards in post-production”, Irish-born Cillian Murphy isn’t joking.

“Like all stars, the Sun will burn out and it will implode and die. We’re just exaggerating that by a few million years for dramatic purposes.”

All becomes clear when you learn that his latest role is in sci-fi thriller Sunshine and the reason he couldn’t look at the Sun is because his character views it from an unusual vantage point – namely, on a spaceship that, a la Pink Floyd, has set its controls for the heart of the Sun. Why? To save the human race, of course.

“Like all stars, the Sun will burn out,” explains Murphy, “and it will implode and die. We’re just exaggerating that by a few million years for dramatic purposes.”

Set in the year 2057, Sunshine’s astronauts are heading towards the Sun, shielded from the worst of the Sun’s rays, on a spacecraft that is a “bomb the size of Manhattan Island”. With a premise as simple as it is compelling, Sunshine is fantastic, cerebral sci-fi in the mould of Alien or Solaris. On directing duties is Manchester’s own Danny ‘Trainspotting’ Boyle, while the screenwriter is Alex Garland, author of best-selling novel The Beach (the film version was directed by Boyle) and the screenplay for Boyle’s 2003 zombie hit, 28 Days Later. A surprise hit internationally, it made Murphy a star, resulting in lead roles in a number of films, including Ken Loach’s Palm d’Or-winning tale of the Irish Civil War, The Wind That Shakes The Barley. Like many an actor before him, Murphy, who turned 30 last year, finds himself beholden to a genre of which he’s not necessarily a fan.

“I did at least grow up absolutely loving Star Wars,” he insists, before admitting, “but I was never into the Star Trek movies or the series really. Like Danny [Boyle], my sci-fi tastes are along the lines of Alien, 2001, Solaris. I went to the ComiCon convention in San Diego which was intense. We did this press conference in front of like, 6,000 fans. It was mad, but you realise that they’re the people who buy the tickets. They’re the people who know these characters as well as you do so you have to make movies that they enjoy.”

Whether fanboys enjoy the movie or not (though I’m guessing they will – Sunshine really is the best sci-fi film in decades), Murphy and his co-stars had a hoot making it. To indicate the co-operation required for humankind’s “last, best hope”, the ensemble cast is deliberately internationalist and includes Michelle Yeoh (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon), Hiroyuki Sanada (The Twilight Samurai) and Chris Evans (not our own carrot-top DJ but The Fantastic Four’s Human Torch). To help the eight ‘astronauts’ bond, they were forced to live together in student accommodation in London.

“It wasn’t supposed to be luxurious and it wasn’t,” chuckles Murphy. “A lot of the time as actors you come in on a Monday morning and the director says, ‘Right, you’ve known each other for ten years.’ And you can do it, you can do the job. There’s that classic scene in Alien where they’re around the table and they get an amazing sense of familiarity. You really believe that they’ve been travelling together in space for however long. We wanted to get that sense as well so the best way to do that, other than actually acting it is to live together and then let the experience inform the performance. We all lived together and ate and cooked and drank together.”

“It wasn’t supposed to be luxurious and it wasn’t,” chuckles Murphy. “A lot of the time as actors you come in on a Monday morning and the director says, ‘Right, you’ve known each other for ten years.’ And you can do it, you can do the job. There’s that classic scene in Alien where they’re around the table and they get an amazing sense of familiarity. You really believe that they’ve been travelling together in space for however long. We wanted to get that sense as well so the best way to do that, other than actually acting it is to live together and then let the experience inform the performance. We all lived together and ate and cooked and drank together.”

As well as recreating what sounds like a Thespian version of The Young Ones, the actors were all sent on an “astronaut bootcamp” which saw them attend lectures, go scuba diving (the nearest we can get to space-walking on Earth) and a trip in a light aircraft to stimulate zero-G.

As well as recreating what sounds like a Thespian version of The Young Ones, the actors were all sent on an “astronaut bootcamp” which saw them attend lectures, go scuba diving (the nearest we can get to space-walking on Earth) and a trip in a light aircraft to stimulate zero-G.

“Humans are not meant to experience this,” says Murphy. “Nothing is, not monkeys or dogs either. It was sickening, horrifying and exhilarating all at the same time.”

Another vital piece of preparation for Murphy was hanging out with the film’s scientific adviser, Dr Brian Cox. Though employed at the Centre for European Nuclear Research, the world’s largest particle-physics laboratory, his varied CV includes a stint as D:Ream’s keyboardist. He doesn’t sound like your typical egghead.

Another vital piece of preparation for Murphy was hanging out with the film’s scientific adviser, Dr Brian Cox. Though employed at the Centre for European Nuclear Research, the world’s largest particle-physics laboratory, his varied CV includes a stint as D:Ream’s keyboardist. He doesn’t sound like your typical egghead.

“No,” agrees Murphy. “He’s not your quintessential physicist by any stretch of the imagination. But he’s so bright and so approachable. I hung out with him for some time and pestered him with idiotic questions about life, the Universe and everything.”

Boyle also used Cox to light-heartedly defend his casting of Murphy, rather than, say, some dweeby brainiac:

“For those who think [Cillian] is a bit good-looking for a physicist, the uncanny thing is that he looks remarkably like our science consultant.”

“He does have a certain boyish charm about him, I’d hand him that,” is all Murphy will bashfully say on the subject.

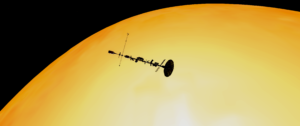

It was Cox who helped Garland and Boyle come up with their sci-fi vision that was “more NASA than Star Wars”. Indeed, Cox even pointed out that Sunshine’s posited scenario – the Sun going nova in the near future rather than in two billion years – could well be possible. The scary thing about scientists is, as Murphy puts it, “how much they don’t know.

“It’s terrifying, or wonderful, depending on how you choose to look at it. They know what five percent of the universe is, but 95 percent of it we don’t have a clue what it is. That’s amazing.”

Thanks to Cox, the science of the movie, which will no doubt make a great DVD extra six months from now, is pretty much watertight. As a result, the spaceship and attendant technology, all feels brilliantly plausible. Even its bomb is theoretically sound.

“While I have no authority to judge it,” Murphy cheerfully admits, “but from what Brian says the idea that you could fire a bomb of dark matter into a star and re-ignite it is possible. They have the equations for it.”